Imports, Exports and Labels

As the U.S. becomes a net importer of agricultural products, Wyoming’s Hageman discusses her meat labeling bill and Benoit says WTO ruling is outdated.

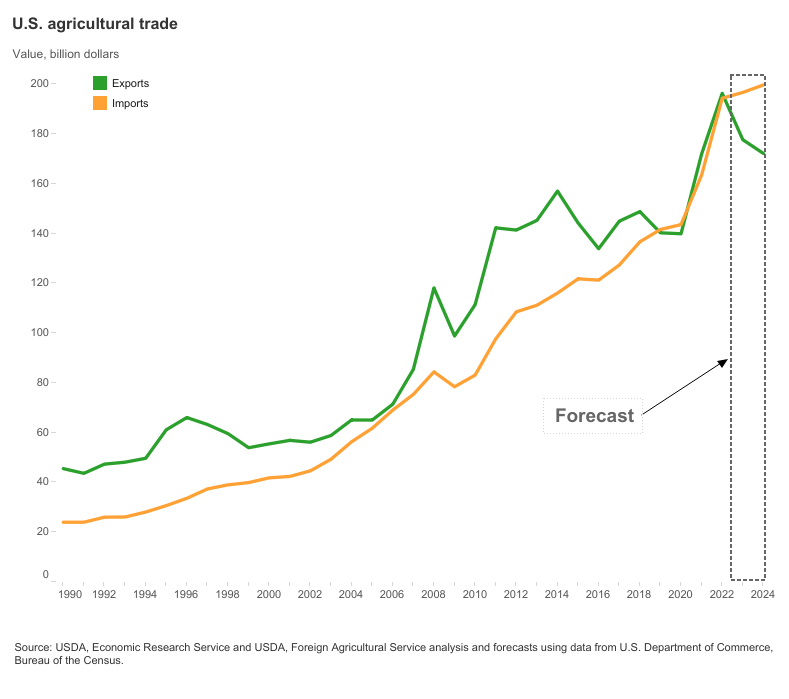

According to a recent USDA report, after 30 plus years of a positive trade balance, the United States will import more dollars worth of agricultural products than it will export.

The imbalance looks to grow larger in 2024.

The lowered export values are “largely driven by lower exports of soybeans, soybean meal, and dairy products” according to the USDA.

For FY 2024, USDA predicts: “Beef exports are forecast to decline $600 million to $8.5 billion on lower volumes due to tight U.S. supplies. Overall livestock, poultry, and dairy exports are projected at $37.6 billion, down $1.4 billion from FY 2023.”

According to another USDA report, Since 2000, U.S. imports of beef have represented about 11 percent of U.S. production and exports about 9 percent. U.S. beef trade is largely dependent on domestic production, and shocks to production can lead to a boost in import demand and a reduction in supplies available for export.

Charles Benoit, a trade attorney currently working for the Coalition for a Prosperous America said the current global trade scenario is not helping production agriculture.

“I don’t mind saying that the emperor has no clothes,” he said. “This system isn’t going to work. Most ag crops are hurt by trade. Fruits, vegetables, seafood, shrimp, lamb, rice. What we have to do is forget about the trading system and go back to what worked.”

Trade is used too often as a political pawn, said Benoit, referencing the dairy industry and the minimal amount of dairy products exported to Canada. “One-third of our organic dairies have folded, dairies are being wiped out, and Congress spends time attacking Canada’s dairies. It will make marginal difference

to American dairies if a bit more milk is exported, but it completely takes over the conversation,” he said.

He also pointed out the decimation of the sheep industry due to imports. The U.S. is now a net importer of lamb, according to USDA statistics.

“It’s completely insane. The message is – other countries will import from us what they need. If exports happen, great, but don’t chase exports, protect a diversified home market. If we can make it here, we should be focused on that,” he said.

Brett Kenzy, a Gregory, South Dakota, cattle producer and backgrounder, and R-CALF USA president, said mandatory Country of Origin Labeling for beef is crucial as the cattle industry looks to keep its head above water in a cutthroat global marketing situation combined with the “global sustainability movement” that threatens the livelihood of the American cattle producer.

He believes that even with the improved prices of the current season, the future of the cattle industry is grim without major changes including MCOOL.

“If ranchers want to have anything to leave to their children, they’re going to have to decide to market their own product,” Kenzy said. “It just seems so obvious to me, globalism is at this point a reality. Another reality is that we haven’t handled it very well. A third reality is that people ARE waking up, but they had also better hurry up.”

Congresswoman Harriet Hageman, just hours after the House failed to muster enough votes to pass its Ag Appropriations bill on Sept. 28, 2023, spoke with TSLN about her bill to implement mandatory country of origin labeling for beef.

The Hageman bill, H.R. 5081 introduced July 28, 2023 and co-sponsored by Gosar (R-AZ), Williams (R-TX), Boebert (R-CO) and Blumenauer (D-OR), would require that all beef bear the country of origin, and that beef can only be marked as product of the USA if it was born, raised and slaughtered in the

United States.

“This is something that has been a priority for me for quite some time,” said Hageman, whose family ranches in the Ft. Laramie and Jay Em communities of Wyoming. “The American public wants to know where their food comes from. We know where our sweaters, cars and purses come from, they deserve to know where their beef comes from. This is a consumer protection bill.”

Hageman said that a “USA” beef label serves a purpose, pointing out that “USA” beef demands a premium in other countries. Meatpackers have an incentive not to label because they are able to garner imported beef at opportune times when cattle prices are high to manipulate the market.

“They can dump massive amounts of foreign beef on the market when they believe it will be the most advantageous to them. We know the cattle market is high right now. They have the ability to manipulate that pretty quickly as long as they can bring in those cattle or beef and claim it is U.S. product,” she

said.

As an attorney, her primary source of income was not production agriculture, yet she has been “closely aligned” with the ag industry, often representing ag producers, she said.

“I’m not opposed to the packers, they have their own interests and they want to make a living in the free market system. I just want to make sure this system is fair,” she said.

Hageman’s bill would fine retailers who mis-label beef at the steep level of $5,000 per pound of beef. She said this isn’t intended to harm small grocers but to keep the meatpackers following the rules.

The Wyoming Representative introduced an amendment to the Ag Appropriations bill this past week that would have prevented USDA from spending money on a mandatory electronic identification program for cattle. While that bill ultimately didn’t pass (after a close voice vote, it died in a roll call vote several hours later), Hagemen said she will be talking to her colleagues to explain her deep concerns with a government-mandated animal identification program. She will simultaneously lobby for her own MCOOL bill, and urges Americans who support MCOOL to also contact their representatives to support her bill.

South Dakota’s Representative Dusty Johnson also introduced HR 5215 to require country of origin labeling for beef in a WTO-compliant manner.

Back in January, South Dakota Senator John Thune and Senators Tester (D-Mont), Rounds (R-SD), Booker (D-NJ), Lummis (R-WY), Gillibrand (D-NY), Hoeven (R-ND) and Lujan (D-NM) introduced

S. 52, The American Beef Labeling Act, in the Senate.

MCOOL for beef was enforced between the years of 2009 and 2015, when Congress repealed the regulation due to a World Trade Organization ruling, which determined that Mexico and Canada would have “permission” to retaliate against the U.S. for its MCOOL law because the MCOOL law put their beef products at a disadvantage in the marketplace.

Since 2015, many lawmakers and organizations have cited the WTO ruling as justification for not implementing MCOOL for beef.

Some studies, including two by Kansas State University professor Glynn Tonsor, have indicated that country of origin labeling for beef did not have a positive effect on cattle prices.

Essentially, said Tonsor, in 2019, “if beef and pork products went through the grocery store, then they had to be labeled. With that (labeling) comes the cost of compliance, which goes into a benefit-cost assessment, and an attempt to quantify the benefit. So what we tried to determine is the impact on the

demand for meat of that law, and ultimately whether there was a positive benefit-cost ratio.”

His research determined that the cost outweighed the benefit and he believes that MCOOL did not increase beef demand, although cattle producers did enjoy high prices during part of the MCOOL implementation period.

“There’s no evidence of a positive demand development following implementation of the law,” Tonsor said of his 2019 study. “So if you don’t have evidence of a benefit, and you do have evidence of a cost, that’s not a desirable benefit-cost ratio.”

The American Farm Bureau worries that the American consumer is not necessarily interested in buying products labeled “made in the USA.” In a 2020 news release, evaluating the renewed interest in MCOOL for beef, the American Farm Bureau pointed out: “While repealed for muscle cuts of

beef and pork and ground beef and pork in 2016, MCOOL remains in place for fresh fruits and vegetables, fish, shellfish, peanuts, pecans, macadamia nuts, ginseng, and ground and muscle cuts of lamb, chicken and goat. Despite the hope that MCOOL would make consumers more likely to purchase U.S.-produced goods, trade data suggests that consumer demand for imported goods remains high. For example, imports of fresh fruits and vegetables were 56 percent higher in 2019 than 2009, despite a strong U.S. industry and increasing ‘buy local’ trends.”

NCBA’s international trade senior director Ken Bacus, told Iowa Farmer Today in 2022 that in the past officials couldn’t come up with a WTO compliant version of the law in six years, so expecting them to come up with some way of making it work in six months is unrealistic. And he says farmers would suffer

if a plan that is not WTO compliant is implemented.

Bacus said the risk of a WTO case is too great.

“That’s a billion dollar gamble for our ag producers,” he said in Iowa Farmer today.

Benoit explains that the WTO ruling isn’t nearly as impactful as it sounds.

Benoit, who grew up in Ottowa, Canada, earned his law degree at Georgetown University, and interned with the Canadian embassy, said that in fact the WTO panel that handed down the COOL decision is no longer even functioning.

“The ranchers were just profoundly unlucky that they were basically the last victim of a terrible WTO decision-making process.”

Benoit said that President Obama, followed by President Trump, and now by President Biden have rejected the decision-making body by refusing to approve any appointees to serve on the panel, rendering it essentially defunct.

Benoit also explained that in 2020, the U.S. Trade Representative published a report on the United States’ concerns with the WTO dispute system in particular with respect to the Appellate Body

(the seven member “board” that made the MCOOL ruling) titled “Appellate Body Errors in Interpreting WTO Agreements Raise Substantive Concerns and Undermine the WTO.”

The USTR went so far as to cite WTO’s MCOOL decision as one of three cases that led to the past three U.S. presidents’ refusal to approve any new members to the WTO body.

“‘Prior to 2012, the Appellate Body had never interpreted Article III to mean that any detrimental impact on like imports is per se sufficient to support a finding of inconsistency.’11 This text cites to footnote 219 of the report, which indicates that the adverse Appellate Body decision on beef labeling was one of just three post-2012 decisions to receive this unjust, unreasonable, and untenable judgment,” explained Benoit in a recent letter to Congress.

Benoit explained that the members of the WTO decision-making bodies tend to be international trade attorneys from around the world. He said they often naturally tend to favor multinational corporations over independent producers simply because larger corporations are their “comfort zone” and many of them are likely employed by multinational corporations or may be seeking future employment there.

While it appeared that Canada and Mexico brought the WTO case, Benoit says that in reality the large meatpackers were the impetus behind it. He points out that Canadian cattle producers are earning less and less of the retail beef dollar and struggling to make a profit, just like American cattle producers are. “If you take a step back here, what happened is that the meatpackers used national sovereignty

to play countries against each other. This happens with other global businesses, too,” he said.

“It’s a real David and Goliath situation where Goliath attracts the people who make decisions on trade disputes,” he said. “I actually walked away from trade law for a while,” he said. “But everything has changed in recent years. I came back into trade. Now we have the momentum to make some real changes,” he said.